Do you find that ice cubes sometimes stick to your warm fingers as that slight moisture in your fingertips instantly freezes on contact with the ice surface? So then, why don’t the webbed feet of ducks, geese, swans, gulls, etc. freeze to the ice?

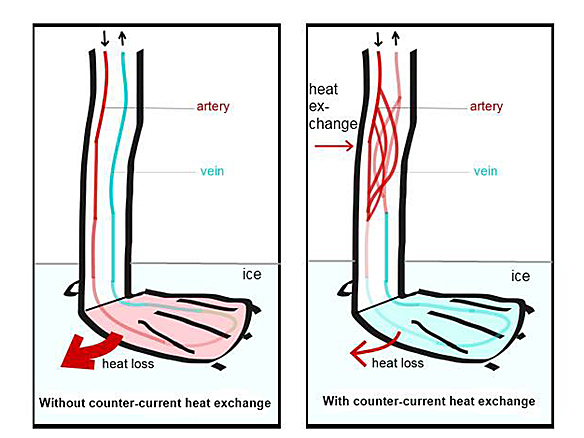

A wonderful adaptation of the circulatory system in the legs, called a counter-current heat exchanger, warms the cold venous blood returning from the foot while it cools the arterial blood flowing to that site. The “exchanger” is actually a network (rete) of arterial blood vessels wrapped around a central vein, and the counterflow between the two sets of blood vessels allows a steep gradient of temperature to be created between the body core and the webbed foot.

With no heat exchange (left), the foot stays warm and loses heat to the ice. A warm web would also stick to the ice! With heat exchange (right), arterial blood going to the foot is gradually cooled by giving up its heat to the vein bringing blood back from the foot. Thus, with heat exchange, foot temperature is about the same temperature as the ice it is resting on. Voila! Less heat loss! [Figures from (Ask a Naturalist)]

Birds have perfected the one-legged stance of the yoga “tree pose” and adopt it frequently when temperatures dip, placing their center of mass directly over one leg and tucking exposed limbs into their plumage.

Trumpeter Swans maintain perfect balance, with their head tucked under a wing for additional protection from heat loss.

On first glance, you might think this was simply an unfortunate, one-legged Ring-billed Gull, But the “tree pose” is used in all activities — whether resting or eating.

At rest, long-legged herons and egrets often tuck one leg up into their belly plumage to reduce heat loss while standing in cold water. Even shorter-legged Black-crowned Night Herons take advantage of this behavioral strategy.

A Broad-winged Hawk sat on a cold steel pole in my backyard one fall morning, and fluffed its belly feathers over its legs as it perched on just one foot (right photo). A few minutes later, when the sun had reached that spot, the bird let the sun do a little warming of its bare legs and feet (left).

Would the one-legged, yoga tree pose work for us, while we wait at a cold bus stop?

Humans posing like trees.

It’s unlikely this would promote heat conservation for humans in cold weather, though.

Fascinating! What interesting information on this phenomenon. . . wonderful photos, too! Now I’m curious – why do we see this so often here in the wetlands of South Florida, where the weather is a balmy 81 today in mid-November?

Water conducts heat away from a warm body faster than air does, so if a bird is standing motionless (i.e., not generating a lot of heat through activity), it would probably want to decrease the heat loss by getting one leg/foot out of the water. Small shorebirds frequently do this while foraging along the ocean shore.

Thanks, Sue! Always interesting and informative to read what you share with readers!

I have wondered about that in the past. Something else I wonder is why wild birds don’t get frost bitten. Chickens and roosters can and do.

Chickens are really tropical birds (at least their ancestors are), and probably aren’t well adapted for extreme cold. Most birds that live in northern temperate climates in winter adjust their circulation and even the makeup of their cell membranes in their legs and feet during the fall to be able to withstand sub-freezing temperatures.

Very interesting! But very comical if I were to try the one legged pose! 🙂